1988 BMW m3 ZAKSPEED 2.5L DTM

Race cars • Historic Race Car • BMW • For sale • France • Paris

Price on ask Published on 25/06/2025 at 18:18 • Langue d'origine FR (Traduire en EN) Traduit en EN (Langue d'origine FR - Afficher)Markus Oestreich

A German driver with an aggressive and consistent style, Markus Oestreich raced for Zakspeed in the DTM with this M3 during the 1988 season. He put in several solid performances against fierce competition, notably the Mercedes 190E and the Ford Sierra RS500. Although he did not win the championship, Oestreich scored important points and contributed to the M3's reputation in the championship.

Hockenheim, September 1989.

Light falls softly on the paddock. The air smells of petrol, hot tyres and dust from the transport trucks. The din of the engines has given way to the silence that is typical of the end of a race day: a mixture of pent-up tension and noble fatigue.

At the end of the driveway, leaning against its hydraulic stand, sits a compact car with widened wings. Its factory white is streaked with traces of rubber, chipped insects and paint chips. It's a BMW M3 Group A, but here we only refer to it by its initials: the M3.

A machine like no other

It doesn't have the arrogance of a racing car. It doesn't try to dominate space. It gently imposes its presence. Its look - those familiar round double headlights - seems more focused than aggressive. Its spoiler, adjusted to the millimetre, doesn't shout. It suggests. It shows nothing, but suggests everything.

A mechanic wipes the bonnet. He doesn't look at it like a machine. He knows it like he knows a horse or an old guitar. He knows that this car has its good days and its bad days. He knows that it likes a clean attack, late braking and long, lean corners. He also knows that it doesn't like rough handling. No sloppy heel-and-toe. No dry transfers. She has to be earned.

The sound of men

A little further on, in the Zakspeed tent, Steve Soper is having a quiet chat with his engineer. They're not talking about engines. They're talking about feeling. About that little flutter at the back as they entered Sachs Kurve. About the hesitation to accelerate again when the rear tyres start to grease. He's not talking about the car as a tool. He's talking about it.

In the paddock, the M3 is a kind of presence. It doesn't just wait for the next round. It inhabits the place. At once discreet and magnetic. An old steward passes by, stops, looks at her, then nods. He must have seen a lot of cars. But this one, he respects. A driver for men

She doesn't need a big name to exist. She likes demanding drivers, not showmen. Whether you're Ravaglia or a young hopeful from the BMW school, she treats everyone the same: she'll tell you exactly what you give her. Nothing more, nothing less. Nothing less.

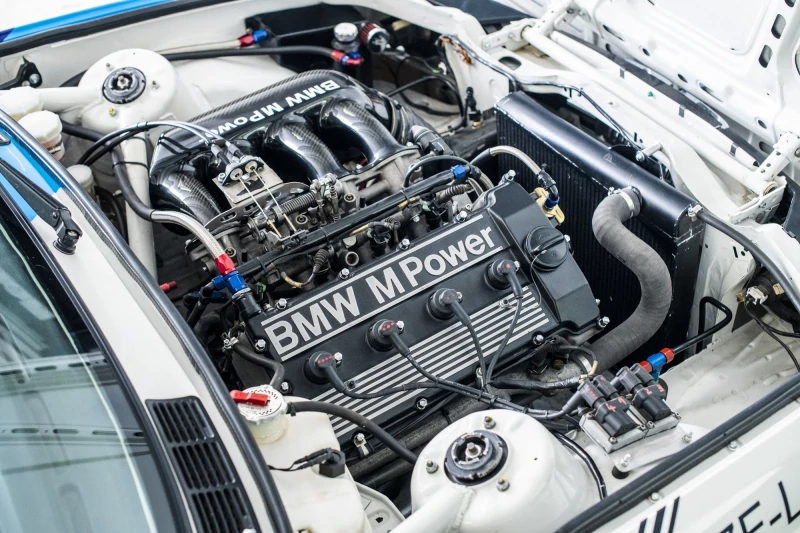

And then there's that noise. That noise. When she slowly pulls out of first gear to go weighing, the S14 engine sputters and then revs up into a metallic, almost raging sound. At high revs, it's like a war clarinet: dry, linear, intoxicating. A soundtrack of discipline. No showboating, no turbo, no panic. Just controlled tension.

Myth is always born in silence

It's in moments like these, when the crowd has gone, that myths take root.

When a silhouette, commonplace to the uninitiated, tells those in the know the story of a whole decade of pure driving, subtle technique and mechanical elegance.

The M3 didn't invent racing. It wasn't the most powerful. It never crushed the competition by sheer force.

But it was the one we listened to, the one we trained, the one we feared - the one we respected.

It's sleeping there now, between two drives, bonnet ajar, with a little heat still in the sheet metal.

And those who drive by know: this car has said it all. And it hasn't finished talking

A few racing anecdotes about the #33 Zakspeed BMW M3 E30 2.5L DTM (Soper-Quester-Dufter) at the 1989 Nürburgring 24 Hours:

"Going from turbo to natural"

Steve Soper described the radical change between his turbocharged Sierra Cosworth (~550bhp) and this M3 (~300bhp):

"The difference was huge... You had to keep the momentum and be nice and gentle with it. If you got nervous... she wasn't quick."

This gentle driving style was crucial on the Nordschleife, in order to preserve grip, brakes and reliability.

Home-grown Zakspeed team advantage

Engineer Steve adds:

"We won... because Zakspeed was based at the Nürburgring, literally on the other side of the road. All our development work was done there.

Having a workshop nearby meant that the car could be set up specifically for the northern loop, a major advantage for the race.

Solidity of the S14 group and thermal choppiness

On the M3 E30 race car, the S14 engine was renowned for its high revs (up to 8,500 rpm). There were frequent episodes of leaks in the exhaust welds:

"The exhaust pipes were deforming by 25 mm at full load; a simple change of silent-blocks stabilised them".

The problem was rectified in time for the race, a testament to BMW's responsive engineering.

Old-school cockpit intact:

Despite the extreme preparation, the cockpit remained spartan: analogue dashboard, mechanical gear lever, little ergonomics, just the essentials in a streamlined cockpit around the roll bar. Soper stresses that it was a pure formula: driver, speed and reliability above all.

With this M3 Zakspeed, they set the fastest lap in class with a time of 9:29.380.

The BMW M3 E30 is still one of the most revered models in the history of the DTM. Its 1988 Zakspeed version, with Oestreich at the wheel, embodies the pinnacle of German racing engineering in the 1980s, with a car that is balanced, responsive and built for the most demanding circuits.

The other ads from Historic Cars